Working with Head and Blood

An exploration of how movement tasks can uncover bodily experiences of ethnographic research

By Marie Hallager Andersen (choreographer and somatic movement practitioner)

& Mette Terp Høybye (medical anthropologist)

Introduction

As a practice ethnography lands somewhere between a craft, an academic discipline and a way of being; much like the somatic practice. The skill of moving freely and uninhibited as the somatic movement system encourages, opens up an inquiry into the body’s intelligence and helps us question our daily bodily experiences. However, while both the dancer and the ethnographer have the body central to the experience of their work, it is rarely debated how the ethnographic fieldwork moves the body and how we should access the tacit, bodily experience as part of our ethnographic process. Movement and ethnography speak to each other and this ‘dialogue’ in our joint collaboration ‘Fieldwork in the Body’ is what we will share in this blog post. We will talk about the themes, questions and findings that theory and practice of ethnography and movement opened up in our joint research.

The central topic of this blog post will be the journey of ‘Blood work’ that informs the three audio files you can explore on the ‘Practice’ page.[1] Before we get to blood, we will begin with a different body part – the head – where our collaboration ‘Fieldwork in the Body’ took off in winter 2018.

Heads: how ethics and vocabulary bridges ethnography and somatic movement

‘Not listening from the two holes on the side of your head but using skin and eyes to absorb and catch richness and diversity in expression. Begin with head, talk with mouth, listen with skin, vibrate with tongue’

Excerpt from Marie’s mark-making in session on ‘heads’, Fieldwork in the Body 2018

We ended our second studio session for ‘Fieldwork in the Body’, where we moved with ethnographic idioms, with an exercise that involved the head. As the time came for us to meet for the third session Mette wrote to Marie:“I might have an idea for what to work with the next time around in the studio. It’s a text about heads – and headhunters (in the literal sense) – and it’s one of the texts that I encountered early on in my studies, which has been profoundly inspirational and troublesome to me.” (Email correspondence 16 February 2018).The text was‘Grief and a Headhunter’s Rage’ by Renato Rosaldo (1983). A short movement task of the head inspired an entire session of movement of/from the head. For our third session we moved around the space leading from the head, we let go of the head and let our partner ‘carry’ it and with these explorations our conversations around ‘heads’ took a new turn. Play with the precarious yet weighty substance of the head and its hierarchically positioned on the top of the body meant our understanding of the Rosaldo text shifted. The interconnection of senses through this movement – at the same time delicate and forceful – lead to conversations of ethics, research and being. Lying on our backs sensing the echoes of the movement task, Marie talked about pulling back from the text, not wanting to be in the space of grief and loss that is so powerfully relayed. Mette shared ethnographic experience of having to hold space for sorrow and loss, pondering the relation between the ethnographic methods and the field imposing itself on the ethnographer.

This studio practice on heads exemplifies one of the most remarkable insights we have gained over the course of our collaboration ‘Fieldwork in the Body’, which is the overlapping of vocabulary between ethnography and somatic movement practice. What is purposein our movement or in our research? How can we move in the studio with our ethnographic research with attentionor intention? Furthermore, the early studio session on ‘heads’ revealed a cross-over of ethics between movement practice and ethnographic practice: what are the boundaries of the body in somatic movement and in anthropology? We explored the physical lines and boundaries of head and body as a relational negotiation, while contemplating the line between field and self.

This studio practice on heads exemplifies one of the most remarkable insights we have gained over the course of our collaboration ‘Fieldwork in the Body’, which is the overlapping of vocabulary between ethnography and somatic movement practice. What is purposein our movement or in our research? How can we move in the studio with our ethnographic research with attentionor intention? Furthermore, the early studio session on ‘heads’ revealed a cross-over of ethics between movement practice and ethnographic practice: what are the boundaries of the body in somatic movement and in anthropology? We explored the physical lines and boundaries of head and body as a relational negotiation, while contemplating the line between field and self.

Blood work

Mette’s work as a medical anthropologist has involved following patients with malignant blood diseases at a haematology ward at a Danish university hospital (Høybye, 2013). Her fieldnotes, interview transcripts, photos and videos from this study as well as other texts about blood, physiological descriptions of blood and the circulatory system became a focal point early in our collaboration.

Mette’s work as a medical anthropologist has involved following patients with malignant blood diseases at a haematology ward at a Danish university hospital (Høybye, 2013). Her fieldnotes, interview transcripts, photos and videos from this study as well as other texts about blood, physiological descriptions of blood and the circulatory system became a focal point early in our collaboration.

Blood and practices of blood (sampling, counting, measuring etc. blood) are central to haematological treatment and care. However, writing up the immediacy, presence and meaning of blood as a profoundly embodied experience, leaves out the bodily experience that is a key part of the research. Text cannot convey the sensory experience of being with blood and patients in the field, which is simultaneously profound and common. How can one communicate the experience of blood as substance divided in bags of plasma and platelets and the infusions given to patients in the clinic in the basement, while shared jokes and stories between staff and patients attempt to mask fatigue, fear and nausea? And what happens to the experience of suddenly being entrusted with keeping a bag of blood platelets in movement between your hands until the nurse arrives to set up the infusion? Weight and tempo suddenly take on new dimensions, literally and emotionally, as your experience of time and space shifts in the presence of sickness and uncertainty. It is impossible to put into writing.

This was where our movement investigation of blood took off in: The gap between the lived

This was where our movement investigation of blood took off in: The gap between the lived

experiences and the communication of the work into the written material. If the profound and essential experiences and ‘bodily materiality’ in the fieldwork was lost in traditional analysis, how could somatic practices and movement reach this?

We sought to set free the written material, the photos and field notes from its confines of

traditional academic form (Høybye 2013), to see what might not have been visible in previous analysis. By pursuing the modes of knowing in the “intrinsic intelligence of the body”(Olsen

2014, p.3), the moving body became both a resource and a tool for understanding the work. The body re-learning to be affected (paraphrasing Latour 2004) in a new move towards and quite literally with the ethnographic material.

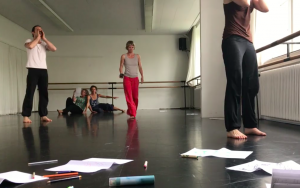

Somatic tasks – placing text in/on the body

As the narrative of working with ‘heads’ in the first part of the post exemplifies, the meaning of a text can change when we engage with it physically. Seeking to get close to experience of blood in the fieldwork of haematological treatment, we utilised methods from somatic movement practices. Marie would initiate these tasks drawing from a range of exercises (in Tufnell & Crickmay 1990; Olsen 2014) and personal experience as a dance improviser and somatic practitioner. One task we used for the blood work was to detach words and sentences from their context. We would speak the field notes out loud into the space to let them land on another moving body: New connections between body and words were created. We would examine how running and jumping would speed up the heart rate and give an internal sense of flow of blood in the body: A bodily understanding of blood flow arose.[2] So, with the ethnographic material freed from its original form, new knowledge emerged, at the same time as a bodily anchor for revisiting previous insights and analysis was produced.

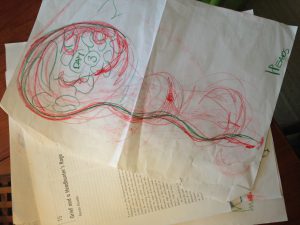

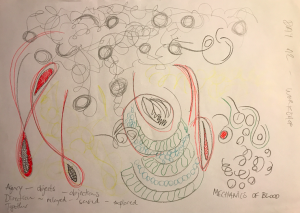

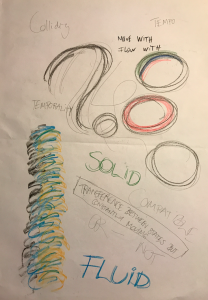

Somatic tasks – Mark-making

Another tool we used during studio sessions was tracking the work through visual and written forms ending each movement task with five minutes of mark-making and writing in silence. The intention was not to produce evidence or analyse movement or even to represent what we did, but to allow a transitional space for the body before entering the ‘talking format’: To

Another tool we used during studio sessions was tracking the work through visual and written forms ending each movement task with five minutes of mark-making and writing in silence. The intention was not to produce evidence or analyse movement or even to represent what we did, but to allow a transitional space for the body before entering the ‘talking format’: To  allow the body to think through the movement of the pen over the paper. As patterns, colours and words materialised on paper through the spontaneous drawing, reflections on the relations of body and text or body and experience appeared as a pre-analytical move. This way we discovered a new sensitivity to the differences and otherness in the blood work. Sensations from the movement task of subtle changes – brought about by a shift in tempo or a subtle switch of weight or touch – could incur an articulation of distinctions in the ethnographic material or the texts concerning blood that had not previously been available.

allow the body to think through the movement of the pen over the paper. As patterns, colours and words materialised on paper through the spontaneous drawing, reflections on the relations of body and text or body and experience appeared as a pre-analytical move. This way we discovered a new sensitivity to the differences and otherness in the blood work. Sensations from the movement task of subtle changes – brought about by a shift in tempo or a subtle switch of weight or touch – could incur an articulation of distinctions in the ethnographic material or the texts concerning blood that had not previously been available.

Somatic tasks – Attention and intention

Our Blood-work on ‘flow’ and ‘solids’ uncovered a parallel to ‘attention’ and ‘intention’. In our movement practice moving ‘in flow’ (the liquidity of the blood) was a way of moving with attention– a way of ‘being fluid and everywhere at once’. In our practice on ‘solids’ (the formed elements of blood carried by the flow) we moved with intention– the quality of the movement and the relation to space was more ‘purposeful’. Tim Ingold (2017) talks about moving into the field with ‘attention, rather than intention’. This line of thinking anchored the somatic work into anthropological terminology in our development of the work in preparation for the audio files. Somatic movement was expanding our ideas of anthropology but simultaneously the theoretical distinction from Ingold added an additional layer of how to understand the practice of attention/intention in the body.

Partial perspectives

Movement is a place to explore human correspondence (Ingold 2017), using movement scores, to form somatic practices that offer ways to advance attention, refine touch and increase sensitivity to the world as a balancing act between self and other (Tufnell 2017): Constantly being reminded as we move, of the impact of our presence and position on the becoming of the world around us that we are part of. The use of movement scores in anthropological work forms an articulate experimentation with perspectives and positions. This holds wide potential for anthropological analysis, as a way to play with how particular positions shape particular realisations and findings in the ethnographic experience. Somatic movement practices clear a path towards turning to the body as a primary source of becoming in the field and throughout the anthropological process and not treating it as a secondary concept simply representing the ethnographer.

As our description and discussion of the becoming of working with ‘heads’ and ‘blood’ illustrates, our collaboration has produced new insights to our individual practices of ethnography or somatic movement. If you make the journey with us through the Blood Work 1-3 audio files, we hope you’ll find inspiration to reflect anew on the connections between tempo, fluidity and solid form in your own research and how embodied realisations of importance may emerge as you move with these reflections.

If you are curious to learn more about our collaboration you could visit this short trailer for ‘Fieldwork in the Body’: https://youtu.be/O2DFLHLwzUI. We also contributed three Extended Practices to the Somatics Toolkit:

Blood work, part 1: Finding your pulse

Acknowledgements

As a product of our collaboration we facilitated a successful workshop in November 2018 inviting both academics and performance artists to participate and explore Blood-work with us and give feedback on the work. We want to thank everyone who participated in the workshops (Nicola Visser, Mette Aakjær, Marco Zavarise, Anna Penati, Ofer Ravid, Melanie Rosen, Alan O’Leary) for engaging with our thoughts and work and contributing their time and reflections.

Footnotes

[1]These will be uploaded 22 March 2019.

[2]You will find a movement task inspired by this in the audio file: Blood Work – part 1: Finding your pulse.

References

Despret V (2004) The Body We Care for: Figures of Anthropo-Zoo-Genesis. Body & Society10 (2–3): 111–34.

Høybye MT (2013) Healing environments in cancer treatment and care. Relations of space and practice in hematological cancer treatment. Acta Oncologica; 52(2):440-6.

Ingold T (2017) On human correspondence. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 23: 9-27.

Latour B (2004) How to Talk About the Body? The Normative Dimension of Science Studies. Body & Society10 (2–3): 205–29.

Olsen, A. with McHose, C. 2014. The Place of Dance.Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press

Rosaldo RI (1983) Grief and a Headhunter’s Rage: On the Cultural Force of Emotions. InText, Play, and Story. The Construction and Reconstruction of Self and Society, edited by Edward M. Bruner, 178–95. Prospect Heights, Illinois: Waveland Press.

Tufnell M (2016) When I Open My Eyes: Dance Health Imagination.Hampshire: Dance Books.

Tufnell M & C Crickmay (1990) Body, Space, Image: Notes Towards Improvisation and Performance. Hampshire: Dance Books.

Comments are closed.